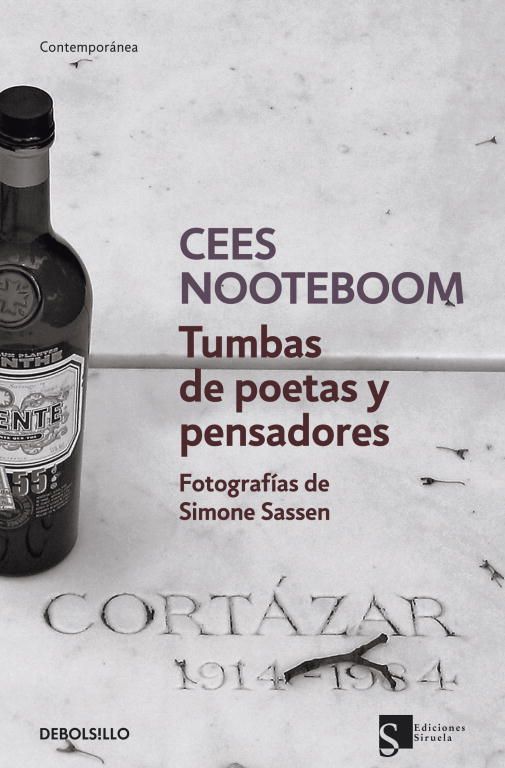

Con motivo de la realización del III Festival Internacional de Poesía de Lima, que se llevará a cabo en la capital del Perú entre el 13 y 16 de abril próximo, conversamos con uno de los poetas más importantes en la actualidad, el holandés Cees Noteboom, quien estará presente en el evento y ofrecerá, sin duda, varias magníficas lecturas de su obra lírica.

Por: Mario Pera

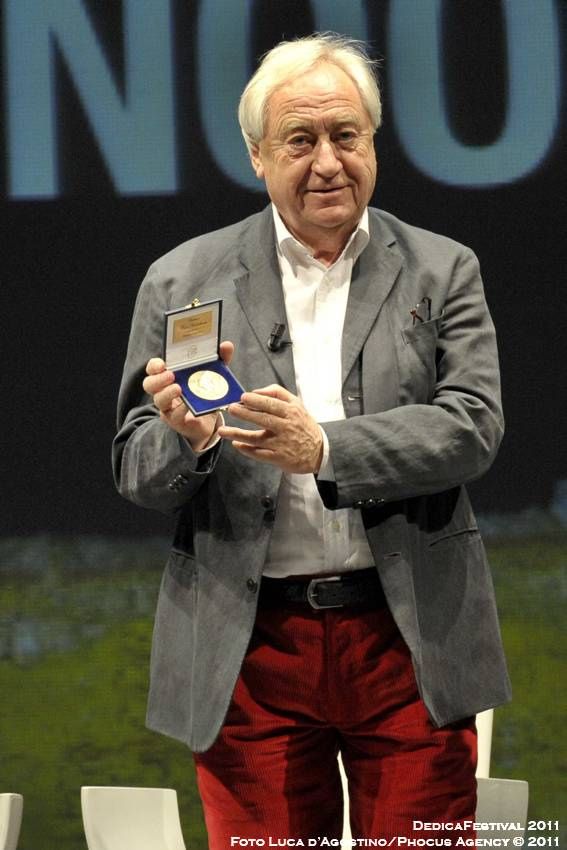

Crédito de la foto: Diario El País /

Bernardo Pérez

«Uno debe recordar que la poesía es un arte».

Entrevista al poeta Cees Nooteboom

Mario Pera [MP]: Cees, tus primeros trabajos te vincularon a la labor administrativa, por ejemplo labores en bancos u otras entidades. ¿Cómo se da tu vínculo con la literatura y, en especial, con la poesía? ¿Consideras que es importante para un poeta, o para quien aspira a serlo, la lectura de textos de poesía o de otros géneros literarios de otros autores? Tal vez sea difícil encontrar un buen escritor sin lecturas.

Cees Nooteboom [CN]: Siempre fui un lector. Mi educación, después de la escuela primaria, fue en colegios religiosos franciscanos y, después de que ellos me epulsaron, agustinos. Allí fue en donde por primera vez me familiaricé con los clásicos Homero, Platón, Ovidio, Jenofonte, Livio, Herodoto, toda la educación literaria. Si mi padre fue lector, no lo sé. Yo era muy joven cuando él murió. Pero fue en los colegios internados en donde empecé a leer todo lo que me estaba disponible en la biblioteca escolar, autores holandeses de los que quizás has oído tales como Couperus, Slauerhoff, van Eeden. Desde que mis padres se separaron, yo me he educado a mí mismo en gran medida en la casa, en donde no había muchos libros.

[MP]:Tu narrativa y tu poesía contienen como elementos sino constantes, al menos muy presentes, temas relacionados a preocupaciones o dilemas existenciales, por ejemplo, la influencia del paso del tiempo en los seres humanos, cómo situaciones como la muerte de los seres queridos o la soledad afectan nuestra vida o cómo la memoria puede ser fuente esencial de la creatividad. En ese sentido, ¿es la poesía la gran respuesta a las mayores interrogantes humanas? Para el poeta Nooteboom, ¿existen algunos temas que todas las excelentes poemas tiene?

[CN]: La poesía es, sin duda, extremadamente importante. También mi preocupación, según tus ejemplos, por el tiempo y por la memoria deben haber estado allí todo el tiempo, sino que se hicieron más evidentes solo cuando comencé a leer en serio a Proust. Cuando uno es joven lee diferentes tipos de poesía y, a menudo, las personas confunden emoción con grandeza o importancia, pero la emotividad genera de manera frecuente mala poesía. Uno debe recordar que la poesía es un arte.

Soy bastante ecléptico en mis gustos, y he traducido a muy diferentes poetas. Mi primer poemario fue publicado en 1956, un año después de mi primera ―y muy poética― novella. Al inicio uno es inocente. Ahora ya no podría escribir ese tipo de poemas, pero uno tiene que aprender. Y la única manera de aprender es el leer. Para resumirlo: la poesía habla de una manera muy personal sobre cosas generales. En tal sentido, el poeta es un hombre común.

[MP]:Comenzaste tu obra literaria como autor de ficción narrativa, de ensayos y de libros de viaje. Si bien pudiste escribir poesía en ese mismo tiempo, recién publicaste tu primer poemario después de tus primeros libros publicados en otros géneros. ¿Esa diferencia es sólo por casualidad o fue algo intencional? ¿Crees que existe una diferencia substancial entre empezar a publicar poesía muy joven o hacerlo ya con ciertas experiencias acumuladas en la vida?

[CN]: Me veo a mí mismo como una institución con tres, o incluso cuatro departamentos; ensayos en arte, piezas de viaje y libros: poesía y ficción. Todos están influenciados mutuamente. He escrito secciones de poemas que se ubican en Bogotá, Ítaca, Lanzartote, pero también poemas sobre Borges o Juarróz o, incluso, Píndaro. Acabo de publicar un libro de viaje sobre El Bosco para los diferentes museos donde están sus pinturas.

En una de mis novelas, dos chicas brasileñas viajan a Australia, no podría nunca haber escrito ese libro (El paraíso perdido) si no hubiera viajado a ambos países. Por otro lado, my libro El canto de ser y apariencia, sucede en parte en Bulgaria, un país que nunca he visitado. Así que, en realidad, no siempre existe ese requerimiento.

[MP]:Desde 1951 realizas viajes alrededor del mundo. A partir de ellos has escrito y publicado numerosos libros de viaje a Túnez, Bolivia, Bahía, Berlín, etc. Hay casos de poetas magníficos que nunca viajaron fuera de su ciudad natal, y también el caso de grandes poetas viajeros. En tu opinión, ¿Qué aportan los viajes, el conocer otras realidades al trabajo poético? ¿Es más importante el mundo interior del poeta o las experiencias a las que este pueda acceder conociendo el mundo?

[CN]: No siempre es intencional. Algunas veces las cosas suceden así. Y sí, hay una diferencia; salvo excepciones como Rimbaud, un poeta aprende viviendo, escribiendo y, sobre todo, leyendo la poesía de otros. Hay muchos tipos distintos de poesía, la diferencia entre Huidobro, Vallejo, Wallace Stevens y Machado es enorme. Un verdadero estilo debe desarrollarse lentamente. La respuesta es la autenticidad. No existen leyes. Puedes no haber salido de tu ciudad, como Kant, y ser un gran filósofo. Lo mismo ocurre en la poesía.

[MP]:En una entrevista comentaste que no tienes recuerdos de tu niñez, que la guerra los borró de alguna manera, quizá como un mecanismo de autoprotección. ¿De alguna manera intentas construir tu pasado, exorcizarlo o recordarlo, a través de tu literatura, y en concreto, de tu poesía? ¿Quizá es la escritura el único medio para sobreponerte al desarraigo en el que has vivido, la vida nómade constante?

[CN]: No soy mi propio psicólogo. La Guerra produce cosas extrañas en las personas. Yo simplemente tengo que enfrentar el hecho que no tengo recuerdos de mi niñez, la que podría haber sido, como en el caso de Proust y Nabokov, un tesoro. Pero tengo que vivir con ello.

[MP]: Desde tus inicios en la literatura te mantuviste alejado de los grupos literarios de tu país, siguiendo un camino en solitario, lo que te llevó a estar por decir de una manera «al margen» de las tendencias de la literatura holandesa, a la cual sin embargo, perteneces. ¿Cómo ha influido esa independencia, esa soledad intencional, en la creación de tu obra literaria? ¿Es la soledad la mejor compañera y musa del escritor?

[CN]: Existe una hermosa expresión en francés: cavalier seul. Cuando estaba en esos colegios religiosos, los otros chicos venían de familias católicas tradicionales. Sin embargo, mis padres estaban divorciados y mi padre murió cuando yo tenía once años; entonces, estoy acostumbrado a arreglármelas por mí mismo. Cuando fui expulsado del último colegio, trabajé en un banco para ganarme la vida. Y tan pronto como pude comencé a viajar alrededor de Eruopa hacienda autostop. Así es como aprendí idiomas. No fui a la Universidad, mis ojos fueron mis profesores. No me arrepiento de ello.

[MP]: A la par de escribir, traduces poesía de importantes autores de la tradición poética española, catalana, francesa y alemana, por ejemplo, para la revista Avenue. ¿Es cierto que todo traductor es traidor? ¿Es necesario que el traductor de poesía sea poeta para intentar conseguir una mejor versión de algo tan complejo como la poesía en otro idioma?

[CN]: No, no suscribo la noción de que los traductores son traidores. Hay muchos poetas que he leído en traducción. Si has leído mi poesía, es solo porque alguien se ha tomado la molestia de traducirla. He intentado revisar las traducciones, las cuales por cierto me ayudan a entender mejor otros idiomas. Antes de ir a Perú debo ir a París, en donde un poemario mío acaba de publicarse. Algunas veces un poema pierde algo en su traducción. Yo, por ejemplo, prefiero leer a Rilke en su propio alemán pero, si no puedo leerlo en su propio idioma, tendría que hacerlo en francés, una melodía distinta. Y viceversa, si Rilke es traducido por Paul Valéry quizá la melodía varía, pero la esencia está ahí.

[MP]: Cees, ¿estás familiarizado con la tradición poética peruana? ¿Quizá algún poeta peruano que hayas leído, o algún poemario, que te parezca notable?

[CN]: Sólo a partir de la lista del festival, he visto que el Perú tiene un ejército de poetas. Es imposible conocer a todos ellos, tanto como es imposible que ellos hayan leído a los poetas holandeses. Hay poetas en todas partes, es una función necesaria, aunque sólo lo sea para las personas quienes pasan su vida haciendo ello [escribiendo poesía].

No obstante, al final la verdadera grandeza llegará a través de. Vallejo vivió en la miseria en París, pero ahora todos conocemos su poesía. El diario El País del Uruguay tiene un suplemento semanas que recibo solo porque algunas veces he publicado un artículo allí. Y, de Nuevo, todas las semanas hay un nuevo poeta uruguayo.

[MP]: Tendremos su visita en Lima en el mes siguiente, para participar en el Tercer Festival Internacional de Poesía de nuestra ciudad capital. En ese sentido, ¿cuáles son sus expectativas con respecto a este festival? ¿Alguna vez has estado en Lima-Perú?

[CN]: Mi expectativa es el escuchar poesía que no he oído antes, experimentar la poeía en sus muchas manifestaciones. Ello es un estilo de vida. En cuanto a ir al Perú, hace muchos muchos años visité Lima. Hay una imagen en mi mente, e intentaré volver a encontrarla. Tiene que ver con la cathedral, un cadaver en el ataúd de un santo. Hace dos años viajé a través del desierto de Atacama. Y si no tuviera que ir a Colombia después del evento, pues Holanda es el país invitado en la Feria Internacional del Libro, hubiera regresado allí. Amo los desiertos, siempre me han inspirado de muchas maneras.

—————————————————————————————————————-

(interview in English version)

By: Mario Pera

«One has to remember that poetry is a craft».

An interview with Cees Nooteboom

Mario Pera [MP]: Cees, your early works were administrative works linked, for example, to banks or other entities, jobs usually far of the literary interests. How do you give your link with literature, and especially with poetry? Do you think it is important for a poet, or to who aspire to be, reading texts of poetry or other literary genres other authors? Maybe it’s difficult to find a good writer without readings.

Cees Nooteboom [CN]: I have always been a reader. My education after primary school was in monastery schools, Franciscans and , after they had sent me away, Augustinians ―there I first became acquainted with the classics, Homer, Plato, Ovid, Xenophon, Livius, Herodotus― all that is literary education. Whether my father was a reader I do not know, I was too young when he died. But at these boarding schools I started to read whatever was available in the school library, Dutch authors that you may never have heard of, Couperus, Slauerhoff, van Eeden. Since my parents had separated, I have largely educated myself, at home there were not many books.

[MP]: Your narrative and your poetry contains as constant elements, or at least very presents, which are related to preoccupations or existential dilemmas, for example, the influence of time in humans, how situations such as the death of loved ones or loneliness affect our life or how memory can be an essential source of creativity. In that sense, is poetry the answer or the way to answer the important human questions? To the poet Nooteboom, they are some topics that all the excellent poems have?

[CN]: Poetry is certainly extremely important. Also my preoccupation with for example time and memory must have been there all along, but only started in earnest when I read Proust. When one is young one reads a different kind of poetry ―very often people confuse emotion with greatness or importance, but emotionality very often makes bad poetry. One has to remember that poetry is a craft. In my tastes I am rather eclectic; I have translated very different poets. My first book of poetry was published in 1956, one year after my first ―and very poetic― novel. In the beginning one is innocent. Now I could not write these poems any longer, but one has to learn. And the only way to learn is to read. To sum it up: poetry speaks in a very personal way about general things. In that sense the poet is an Everyman.

[MP]: You began your literary work as author of narrative fiction, essays and travel books. Maybe you wrote your poetry at this same time, but you published your first book of poetry after your narrative and travel first books published. This difference is caused only by chance or was it intentional? Do you think that there is a substantial difference between begin to publish poetry in a very young age or do it when you already accumulated certain experiences in life?

[CN]: I see myself as an institution with three, or even four departments; essays on art, travel pieces and books, poetry, fiction. They all influence one another. I have written poems set in Bogota, Ithaca, Lanzarote, but also poems about Borges or Juarroz or even Pindaros ―I have just published a travel book on Hieronymus Bosch; to the different museums where his paintings are. In one of my novels two Brazilian girls travel to Australia: I could never have written that book (Lost Paradise – El paraíso perdido) if I had not travelled in both countries. On the other hand my book El Canto de Ser y Apariencia was set partly in Bulgaria, a country I never visited. So to have been actually there is not always required.

[MP]: Since 1951 you do a lot of trips around the world. From them you have written and published numerous travels books for example to Tunisia, Bolivia, Bahia, Berlin, etc. There are cases of great poets who never traveled outside their hometown, and also the case of great traveler poets. In your opinion, what provides the travels or to know other realities to the poetic work? To the poetry it’s more important the inner world of the poet or the experiences he can have traveling around the world?

[CN]: There is not always intention. Sometimes things just happen like that. And yes, there is a difference; apart from exceptions like Rimbaud a poet learns by living, writing, and above all reading the poetry of others. There are many different kinds of poetry, the difference between Huidobro, Vallejo, Wallace Stevens and Machado is enormous. A true style has to develop slowly. The answer is authenticity. There are no laws. You can never leave your town, like Kant, and be a great philosopher. The same goes for poetry.

[MP]: In an interview mentioned that you do not have memories of your childhood, that maybe the war and your fear have erased somehow your memories, perhaps as a mechanism of self-protection. Would somehow you try to build your past, remember or even get exorcize your fears through your literature, and specifically, of your poetry? Perhaps writing is the only way to get over the rootlessness in which you lived, the constant nomadic life?

[CN]: I am not my own psychologist. War does strange things to people. I simple have to confront the fact that I have no early childhood memories ―which could have been, as in the case of Proust and Nabokov, a treasure house. But I have to live with that.

[MP]: From your beginnings in literature you kept away from literary groups in your country, following a path alone, what led you to be maybe «outside» of trends of Dutch literature, to which no But you belong. How has this independence influenced, or this intentional loneliness, in creating your literary work? Is loneliness the best companion and muse of the writer?

[CN]: There is a beautiful expression in French: cavalier seul. When I was in these monastery schools, the other boys came from traditional catholic families. But my parents were divorced, and my father died when I was 11, so I have been used to fend for myself. When I was kicked out from the last school I worked in a bank to earn my living. And as soon as I could I started hitchhiking around Europe. That is how I learned my languages. I did not go to University, my eyes were my professors. I do not regret this.

[MP]: Along with writing, you are translator of poetry of important authors of the poetic Spanish, Catalan, French or German tradition, for example, for the magazine Avenue. It’s true that everything translator is a traitor? Is it necessary that the poetry translator be also a poet to try to get a better version of something as complex as poetry in another language?

[CN]: No, I do not subscribe to the notion that translators are traitors. There are many poets that I have read in translation. If you have read my poetry it is only because somebody has taken the trouble of translating them- I try to check the translations, which by the way helps me to understand other languages better. Before coming to Peru I have to go to Paris, where a book of my poetry has just been published. Sometimes a poem will lose something in a translation, I for example prefer to read Rilke in his own German, but if I could not read him in his language I would have to do with French, a different melody. And vice-versa: Rilke translated Paul Valéry ―maybe the melody varies, but the essence is there.

[MP]: Cees, are you familiar with the Peruvian poetic tradition? Perhaps some Peruvian poet you’ve read, or some poetry book, that it seems you remarkable?

[CN]: Only from the list of the festival I have seen that Peru has an army of poets. It is impossible to know them all, just as impossible that they could read Dutch poets. There are poets everywhere; it is a necessary function, if only for the people who spend their life doing this. But in the end true greatness will come through. Vallejo lived in misery in Paris, but now we all know his poetry. El País Uruguay has a weekly supplement that I receive because sometimes I publish an article there. And again: every week a new Uruguayan poet.

[MP]: We will have your visit in Lima in the next month, to participate in the Third International Poetry Festival of our capital city. In that sense, what are your expectations regarding to this festival? Have you ever been in Lima-Peru?

[CN]: My expectation is to hear poetry I have not heard before, to experience poetry in its many manifestations. It is a way of life. As to coming to Peru, I have many many years ago visited Lima. There is one image in my mind, and I will try to find it back. It has to do with the cathedral, a corpse of a saint in a coffin. Two years ago, I travelled through the Atacama Desert. And if I do not have to go to Colombia after this – where Holland is the guest-country of the international book fair, I would have gone back there now. I love Deserts; they have all ways inspired me.